HANNIBAL, MISSOURI

Like unto Samuel Clemen’s legendary protagonist, Tom Sawyer, Alex Addison, the present-day, barefoot ambassador of Hannibal, is all business. “I see [riding the economic downturn] not as a challenge but as a goal – it’s starting to click, [things locally are] going to be really good,” explained Alex, age 13, holding his own in a round-table interview with Mayor Roy Hark, Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Terry Sampson, and City Planner Jeff LaGarce.

Taking a day out of his busy schedule as Hannibal’s official “Tom”, Alex took me for a tour of ‘America’s Hometown’ with the polished grace of a professional politician. Together, we visited everybody from the local, modern-day judge, to the minister, to of course, the city’s old-school mayor.

As we talked about the building blocks of America – of what made America great – I learned that Twain’s literature, along with a now bustling Main Street, is making all the difference, at least locally here in ‘America’s Hometown’. There is a buzz in the air along Main Street, as shopkeepers brave the financial crisis in hopes of a year that for many is landing solidly in the black.

The trick, as far as I could see, was a love and rallying cry from business owners and citizens alike to preserve the downtown district. “Preservation doesn’t cost – it pays,” exhorted local resident and former PBS television personality, Bob Yapp.

After traveling the world as a foremost expert on home restoration, with his own show on both PBS and NPR, Mr. Yapp decided to settle for good here in Hannibal, describing himself as one of “Hannibal’s expats” who “are coming to Hannibal [with a love of Hannibal’s] architecture.”

But it isn’t just Mr. Yapp’s generation of eclectic friends, ranging from potter Steve Ayers to the next-door Bed and Breakfast innkeepers of the Dubach Inn, that are excited about restoring America’s architectural past. Yapp is busy mentoring and teaching at-risk youth from the local high school, many of which enjoy their time “on site” so much they plan to take up the trade. “I actually want to do exactly what Bob is doing,” explained one Hannibal High School student, going on to exhort, “when you’re here you actually get to do stuff and work on stuff that you actually want to do.”

Which could describe the new Mark Twain Boyhood & Museum Executive Director Cindy Lovell’s take on Hannibal to a tee, self-describing her time in this town as “being intoxicated with the history [of Twain] ever since stepping foot into Hannibal.” Dr. Lovell’s eyes glance around her as she walks these streets – observing the very homes and hills and river and buildings that directly inspired Hannibal’s favorite son – Mark Twain – with an all-knowing smile that one can’t help but find contagious. “I think Hannibal’s history is so linked to the past,” continued Dr. Lovell, “in the preservation of the past, the lessons we learn from the past. And we have to be vigilant.”

From the city officials I was most fortunate to meet, to the next generation of high school artisans, I believe that Hannibal, and through her example, America’s hometowns around the country, will continue to experience a re-birth of sorts as revitalization begins to hold sway. “Across the nation, small communities are reinventing themselves,” continued Mr. Yapp. “And they’re having a renaissance in the sense that… things change.”

Continuing that walk, Dr. Lovell looked up, gesturing to the top of Main Street. “Tom always has his eye on the future,” explained Dr. Lovell. “That’s why when you look at the statue of Tom and Huck, lording over Main Street from the base of Cardiff Hill, you will see Tom stepping into the future.”

“Not only do we have a good past,” explained young Alex Addison, “but I think it would be better to have a good past and a great future than a great past and an okay future.” A future that judging from the next generation of Hannibal, is most certainly going to be bright.

Pam Ritchie, Executive Director of the Opportunity Center and the former chair of Prairie du Chien’s Main Street Revitalization Project refers to her work as “community cultivation.” As she explains, “There are a lot of stories [from] many, many years ago about what Prairie du Chien looked like on a Friday night and it was lined with farmers in overalls and families on the streets – talking, gathering together, doing their shopping for the week – spending their money locally and supporting these businesses which in turn supported them.”

Pam Ritchie, Executive Director of the Opportunity Center and the former chair of Prairie du Chien’s Main Street Revitalization Project refers to her work as “community cultivation.” As she explains, “There are a lot of stories [from] many, many years ago about what Prairie du Chien looked like on a Friday night and it was lined with farmers in overalls and families on the streets – talking, gathering together, doing their shopping for the week – spending their money locally and supporting these businesses which in turn supported them.” sustainable food practices to the bright young learners at Prairie du Chien’s B.A. Kennedy Elementary School.

sustainable food practices to the bright young learners at Prairie du Chien’s B.A. Kennedy Elementary School. and with that they were able to hire an executive director and create a membership of both downtown businesses and community members.”

and with that they were able to hire an executive director and create a membership of both downtown businesses and community members.” sustainable community [is] a community that … feeds itself, if you will, that keeps its energy churning and building here rather than going elsewhere.”

sustainable community [is] a community that … feeds itself, if you will, that keeps its energy churning and building here rather than going elsewhere.”

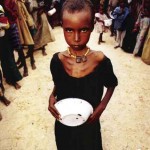

“They heard rumors of a famine creeping across southern Somalia, [and] they wanted to visit the region themselves and see if there was any truth to the stories,” explained Kathy Eldon, Dan’s mother. “[He] was in Kenya for the summer, before returning to UCLA that autumn to continue his studies, [and] was utterly stunned by what he saw – hundreds of dead and dying women, children, and old people; thousands displaced in a desperate search for food. Although barely able to view the horrors unfolding before him, he shot them with his camera and they were among the first to be seen by a global audience. Moved by the response to his images, Dan returned again and again to Somalia, recording the aid that flowed into the country- and its decline into chaos. He never returned to UCLA.”

“They heard rumors of a famine creeping across southern Somalia, [and] they wanted to visit the region themselves and see if there was any truth to the stories,” explained Kathy Eldon, Dan’s mother. “[He] was in Kenya for the summer, before returning to UCLA that autumn to continue his studies, [and] was utterly stunned by what he saw – hundreds of dead and dying women, children, and old people; thousands displaced in a desperate search for food. Although barely able to view the horrors unfolding before him, he shot them with his camera and they were among the first to be seen by a global audience. Moved by the response to his images, Dan returned again and again to Somalia, recording the aid that flowed into the country- and its decline into chaos. He never returned to UCLA.” “I learned that when you’re a journalist, you get to save people’s lives,” explained Ruqiya. “Not physically, but emotionally – because there’s people

“I learned that when you’re a journalist, you get to save people’s lives,” explained Ruqiya. “Not physically, but emotionally – because there’s people President Abdirahman Mohamed Mohamud‘s question to the girls and their class was if they had plans to come back to Somalia. The girls told me that they smiled broadly when asked this question, answering together, in unison: “Yes, we do want to go back to Somalia … We want to make a difference.”

President Abdirahman Mohamed Mohamud‘s question to the girls and their class was if they had plans to come back to Somalia. The girls told me that they smiled broadly when asked this question, answering together, in unison: “Yes, we do want to go back to Somalia … We want to make a difference.” (11/28/07)

(11/28/07) Starting from the Brian Coyle Center of the University of Minnesota where Somali children of all ages worked on computers, talked music, and played basketball, we moved through the inner-city landmark of Cedar-Riverside Plazas, a low-income housing set of buildings – all colorful beyond belief – which have been reclaimed from a once drug/gang infested stronghold. “You used to not be able to enter that area,” explained Ms. Hakeem, who ran for City of Minneapolis Mayor back in 2005 under the Green Party banner. “But now you can walk around freely, even at 10pm at night. When the Somali refugees began to arrive, they naturally moved into the least expensive section of town – Cedar-Riverside.”

Starting from the Brian Coyle Center of the University of Minnesota where Somali children of all ages worked on computers, talked music, and played basketball, we moved through the inner-city landmark of Cedar-Riverside Plazas, a low-income housing set of buildings – all colorful beyond belief – which have been reclaimed from a once drug/gang infested stronghold. “You used to not be able to enter that area,” explained Ms. Hakeem, who ran for City of Minneapolis Mayor back in 2005 under the Green Party banner. “But now you can walk around freely, even at 10pm at night. When the Somali refugees began to arrive, they naturally moved into the least expensive section of town – Cedar-Riverside.”  Part of learning about pride in your community comes from actively pitching in to help it out. As we moved along the streets and under the bridges, Ayan and Mary introduced me to their latest community project – a mural of Minneapolis they are working on in conjunction with “Articulture”. Here, Executive Director Elizabeth Greenbaum explained that when it comes to at-risk kids mixed with art, “art is a wonderful equalizer, especially for students who don’t succeed in other subject matters. When you think about it and take it a step further, we’re talking about the basic understanding and the basic concepts to write – and that leads into reading and that leads into learning – so [the] arts are very much orientated to learning on all levels.”

Part of learning about pride in your community comes from actively pitching in to help it out. As we moved along the streets and under the bridges, Ayan and Mary introduced me to their latest community project – a mural of Minneapolis they are working on in conjunction with “Articulture”. Here, Executive Director Elizabeth Greenbaum explained that when it comes to at-risk kids mixed with art, “art is a wonderful equalizer, especially for students who don’t succeed in other subject matters. When you think about it and take it a step further, we’re talking about the basic understanding and the basic concepts to write – and that leads into reading and that leads into learning – so [the] arts are very much orientated to learning on all levels.” thought about the mural, now bordering one side of the building his shop inhabits. Without thinking, he simply said, “I think it’s a great idea. I’m very impressed with the groups of people who go there.” When asked how the old-school, predominately German and Swedish community is adapting to the large influx of Somali refugees, Jim thought before explaining, “While most people are okay with it, overall I think a lot of the seniors aren’t adapting.” Although he was quick to point out that after all, these same old timers had once been immigrants as well.

thought about the mural, now bordering one side of the building his shop inhabits. Without thinking, he simply said, “I think it’s a great idea. I’m very impressed with the groups of people who go there.” When asked how the old-school, predominately German and Swedish community is adapting to the large influx of Somali refugees, Jim thought before explaining, “While most people are okay with it, overall I think a lot of the seniors aren’t adapting.” Although he was quick to point out that after all, these same old timers had once been immigrants as well.  Relay for Life is in association with the

Relay for Life is in association with the  At the age of 36, one town cancer survivor, Kathie Smith, a mom of two young children, explained that it was Austin Price, a young boy who was diagnosed with cancer at age 4 1/2, who “paved the way for my kids to handle me being diagnosed with cancer.” “I graduated from high school together with [Austin’s mom] and Austin was in day care with my children. He taught my kids that just because you have cancer [it] doesn’t mean it’s fatal.” Somewhat of a living legend here in Aitkin, Austin, now age 6, has survived a year following eight months of hospitalization and treatment down at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis. “He’s made it,” beamed Kathie, fighting back tears.

At the age of 36, one town cancer survivor, Kathie Smith, a mom of two young children, explained that it was Austin Price, a young boy who was diagnosed with cancer at age 4 1/2, who “paved the way for my kids to handle me being diagnosed with cancer.” “I graduated from high school together with [Austin’s mom] and Austin was in day care with my children. He taught my kids that just because you have cancer [it] doesn’t mean it’s fatal.” Somewhat of a living legend here in Aitkin, Austin, now age 6, has survived a year following eight months of hospitalization and treatment down at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis. “He’s made it,” beamed Kathie, fighting back tears. When asked for advice for others who might be fighting for their very lives around the world, Austin, moving between examining the camera and sitting on his mother’s lap, rubbed his head before answering: “Be strong” – to be followed by the simple, hard fought admonition – “be brave.”

When asked for advice for others who might be fighting for their very lives around the world, Austin, moving between examining the camera and sitting on his mother’s lap, rubbed his head before answering: “Be strong” – to be followed by the simple, hard fought admonition – “be brave.” “It was a surprise to get the award from the Minnesota Small Business Administration but also a bigger surprise to be invited to Washington D.C.,” explained Mr. Wells. Upon arrival to the White House with small business award winners from different states, Andy was seated in front as a ‘special guest’ – a guest whom President Obama would address in his speech on the “courage and determination and daring” of great leaders, stating: “It’s what led Andy Wells, a member of the Red Lake Ojibwa Tribe to invest $1300 back in 1989 to found Wels Technology, manufacturing industrial tools and fasteners, and creating jobs near reservations in Minnesota, where he lives.”

“It was a surprise to get the award from the Minnesota Small Business Administration but also a bigger surprise to be invited to Washington D.C.,” explained Mr. Wells. Upon arrival to the White House with small business award winners from different states, Andy was seated in front as a ‘special guest’ – a guest whom President Obama would address in his speech on the “courage and determination and daring” of great leaders, stating: “It’s what led Andy Wells, a member of the Red Lake Ojibwa Tribe to invest $1300 back in 1989 to found Wels Technology, manufacturing industrial tools and fasteners, and creating jobs near reservations in Minnesota, where he lives.” Upon arrival at Wells Technology, which doubles as Wells Academy, it struck me as an interesting concept to put a classroom front and center in the headquarters of a main business office. “Every day is an open house,” explained Mr. Wells. “Every day we’ve got a busload of reservation kids or church groups or even car enthusiast clubs coming around. When the busses pull up you can see who the tough kids are – the ones who smoke a cigarette outside before coming in and hang their head in the classroom. But when we start to show them how our products help shoot flares out of military helicopters and other interesting things, they perk up – they start to ask questions – they start to understand why it is important to learn about math and science.”

Upon arrival at Wells Technology, which doubles as Wells Academy, it struck me as an interesting concept to put a classroom front and center in the headquarters of a main business office. “Every day is an open house,” explained Mr. Wells. “Every day we’ve got a busload of reservation kids or church groups or even car enthusiast clubs coming around. When the busses pull up you can see who the tough kids are – the ones who smoke a cigarette outside before coming in and hang their head in the classroom. But when we start to show them how our products help shoot flares out of military helicopters and other interesting things, they perk up – they start to ask questions – they start to understand why it is important to learn about math and science.” “There is book learning and there is other wisdom,” explained Mr. Wells, referring to the system of ‘elders’ within the Native American community. “The [positive] influences began in my life early – it was neighbors, my parents, my grandparents … A neighbor friend, named Charlie Barrett, who really had no formal education but was a very humble neighbor noticed me running ahead of the adult groups quite often and he said to me, ‘Why don’t you open the door for people when you’re up there.’ At the time I thought he meant the physical door but now when I look back, maybe he meant more. Maybe he was a wise fellow like many of the wise people I’ve met, and he could see that perhaps one day I would be able to open doors of opportunity for people – and now that’s one of my main missions in life – to continue doing things that help other people because so many have helped me.”

“There is book learning and there is other wisdom,” explained Mr. Wells, referring to the system of ‘elders’ within the Native American community. “The [positive] influences began in my life early – it was neighbors, my parents, my grandparents … A neighbor friend, named Charlie Barrett, who really had no formal education but was a very humble neighbor noticed me running ahead of the adult groups quite often and he said to me, ‘Why don’t you open the door for people when you’re up there.’ At the time I thought he meant the physical door but now when I look back, maybe he meant more. Maybe he was a wise fellow like many of the wise people I’ve met, and he could see that perhaps one day I would be able to open doors of opportunity for people – and now that’s one of my main missions in life – to continue doing things that help other people because so many have helped me.”

Veterans, the youth, women, and elders are all honored at this traditional pow wow, now celebrating its 47th year, in multiple ways. Many of which are sacred and cannot be recorded by camera or sound. For example there are the songs of the drums. Each drum possesses within it a song which is special – a song within that only that drum can play.

Veterans, the youth, women, and elders are all honored at this traditional pow wow, now celebrating its 47th year, in multiple ways. Many of which are sacred and cannot be recorded by camera or sound. For example there are the songs of the drums. Each drum possesses within it a song which is special – a song within that only that drum can play. What makes this particular pow wow special is that it features approximately 300 dancers and concentrates on the old and the young. My take for a story was to attempt to document how the knowledge of the dance is passed down from the old to the young, from generation to generation.

What makes this particular pow wow special is that it features approximately 300 dancers and concentrates on the old and the young. My take for a story was to attempt to document how the knowledge of the dance is passed down from the old to the young, from generation to generation. And funny enough, when I spoke with Andrew Wakonabo, a winning boy crowned “Mii-Gwitch Mahnomen Brave” from last year, he said the same thing, explaining, “I pretty much learned myself – watching other people dance.” The winning dancers are crowned “brave” and “princess” and their title is more complicated than simply wearing a crown and a banner. Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Councilman Joe Gotchie explained that once they win, for the entire year they must “demonstrate responsibilities [so] that other youth look up to them.”

And funny enough, when I spoke with Andrew Wakonabo, a winning boy crowned “Mii-Gwitch Mahnomen Brave” from last year, he said the same thing, explaining, “I pretty much learned myself – watching other people dance.” The winning dancers are crowned “brave” and “princess” and their title is more complicated than simply wearing a crown and a banner. Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Councilman Joe Gotchie explained that once they win, for the entire year they must “demonstrate responsibilities [so] that other youth look up to them.” There’s a bond between the old and the young within the Native American community that other cultures can learn from. The Ojibwe historically used complex pictures on sacred birch bark scrolls to communicate their knowledge.

There’s a bond between the old and the young within the Native American community that other cultures can learn from. The Ojibwe historically used complex pictures on sacred birch bark scrolls to communicate their knowledge.