ST. LOUIS, MO

Alfton Denise Jackson, a single mother of two young boys, was in tears when the news came through that she had qualified for a new home. “I received a letter from my case worker,” reported Ms. Jackson, “stating it was a program to build your own home and if I was interested in the program, to come to the site.”

The “site” is one of the largest Habitat for Humanity projects in Habitat St. Louis’ history, encompassing twenty-four new homes for this year, adding up to ninety-one total for the Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood alone.

The “site” is one of the largest Habitat for Humanity projects in Habitat St. Louis’ history, encompassing twenty-four new homes for this year, adding up to ninety-one total for the Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood alone.

The Jeff-Vander-Lou district of Mid Town St. Louis is historic – first and foremost due to the fact it was the first place in St. Louis where African Americans were allowed to own property. Explains Habitat for Humanity St. Louis Director of Resources, Courtney Simms, “A lot of African American businesses were down in the corridor … a couple of blocks over, so to be able to come into this neighborhood and build homes… is quite significant.”

Alexander, age 12, and Ledra, age 7, the two young sons of home-builder Alfton Denise Jackson, are excited about the family’s new prospects. Their reasons are first for safety, and second because they will now each have their own bedrooms. “We used to live next to a man who would beat on his wife,” explained Alexander. “But now we’re moving to a safer place.”

Alexander, age 12, and Ledra, age 7, the two young sons of home-builder Alfton Denise Jackson, are excited about the family’s new prospects. Their reasons are first for safety, and second because they will now each have their own bedrooms. “We used to live next to a man who would beat on his wife,” explained Alexander. “But now we’re moving to a safer place.”

When asked if the present neighborhood where Ms. Jackson, Alexander, and Ledra now reside is safe, Alfton was quick to reply, “No … We [currently] stay in some nice apartments in an area [St. Louis] is trying to build up around here but we’re right next to some of the projects … it’s somewhat scary but [although] we [have] learned to cope with it … it’s not a place I would want to raise my kids because it’s kind of dangerous.”

Asked if he was at times scared of his present location in life, Alexander reported, “Yes. There was a shooting,” going on to explain there are gunshots nearby that ring out at night.

Asked if he was at times scared of his present location in life, Alexander reported, “Yes. There was a shooting,” going on to explain there are gunshots nearby that ring out at night.

The Jackson family are gregarious and affable. They smile frequently, and it’s not only for the camera. There is a love and a bond that one can readily detect. Alfton is quick to tell me of her sons’ recent school honors, of “all E’s” and awards, and of a hushed thankfulness that her sons are so fond of their school – a school they will not have to change when they move into their new home in Jeff-Vander-Lou come late November. Catch phrases like “peaceful” and “pride” and even “college” are part of her young boys’ vocabulary. As is an excitement for a future they are proud to step into.

Looking around the Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood, it is exciting to see a community quite literally on the rise, rolling up their shirtsleeves in an effort to reclaim a past pride, a past history that folks around here point to with symbolic reverence. There are the odd dilapidated structures of days gone by, before the factory jobs moved out of town. There are a large number of vacant lots, and amidst the vacancies there is a whole new community that is quickly taking shape, rising up from the dust.

Looking around the Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood, it is exciting to see a community quite literally on the rise, rolling up their shirtsleeves in an effort to reclaim a past pride, a past history that folks around here point to with symbolic reverence. There are the odd dilapidated structures of days gone by, before the factory jobs moved out of town. There are a large number of vacant lots, and amidst the vacancies there is a whole new community that is quickly taking shape, rising up from the dust.

Driving up and down the streets, Courtney Simms smiles broadly as she explains which new homes were built in which year, which vacant lots are owned by Habitat, as well as an impressively large row of homes, set out on multiple city streets, which are currently under construction. She takes a genuine pride in her work, showing and explaining the LEED Certified achievements of the new Habitat homes, of where a holistic approach to plotting and planning is merging cost saving features with the natural environment. “When you consider that … where these houses [now sit] were vacant lots and now they’re thriving families that will be raising their children … [we are together] rebuilding the community.”

And yet while folks are hopeful, the fact is that the recent history of Jeff-Vander-Lou is not exactly rosy, as seen most readily in the multiple stop signs strapped with stuffed teddy bears, of stuffed dolls of various shapes and sizes, pinpointing the intersections where children from the neighborhood have at some point in time lost their lives.

And yet while folks are hopeful, the fact is that the recent history of Jeff-Vander-Lou is not exactly rosy, as seen most readily in the multiple stop signs strapped with stuffed teddy bears, of stuffed dolls of various shapes and sizes, pinpointing the intersections where children from the neighborhood have at some point in time lost their lives.

Which is where the desire for hope and for change have caught fire, where the sense of community, at least locally, is making a sincere power play. Where “ninety-one thriving families” are most certainly coming together, hammers in hand via Habitat for Humanity, made up of volunteers from CEO’s to Senior Vice Presidents to the average, typical “Joe” – together here unified, quite busily making a stand.

2006 Habitat homebuyer Wendy McPherson, who is now volunteering as a “mentor” to Alfton Denise Jackson, amongst others, explained the phenomenon of what is happening here best by bringing the word ‘community’ down to its brass tax. Explains Wendy, “It says a lot about ‘community’ because it teaches your neighbors to come together as one and not just be next door – but to get involved … It helps others to become more aware of their surroundings and to draw together as a community and work together. It makes a difference when you know your neighbors and you look out for your neighbors and everyone comes together.”

2006 Habitat homebuyer Wendy McPherson, who is now volunteering as a “mentor” to Alfton Denise Jackson, amongst others, explained the phenomenon of what is happening here best by bringing the word ‘community’ down to its brass tax. Explains Wendy, “It says a lot about ‘community’ because it teaches your neighbors to come together as one and not just be next door – but to get involved … It helps others to become more aware of their surroundings and to draw together as a community and work together. It makes a difference when you know your neighbors and you look out for your neighbors and everyone comes together.”

Pam Ritchie, Executive Director of the Opportunity Center and the former chair of Prairie du Chien’s Main Street Revitalization Project refers to her work as “community cultivation.” As she explains, “There are a lot of stories [from] many, many years ago about what Prairie du Chien looked like on a Friday night and it was lined with farmers in overalls and families on the streets – talking, gathering together, doing their shopping for the week – spending their money locally and supporting these businesses which in turn supported them.”

Pam Ritchie, Executive Director of the Opportunity Center and the former chair of Prairie du Chien’s Main Street Revitalization Project refers to her work as “community cultivation.” As she explains, “There are a lot of stories [from] many, many years ago about what Prairie du Chien looked like on a Friday night and it was lined with farmers in overalls and families on the streets – talking, gathering together, doing their shopping for the week – spending their money locally and supporting these businesses which in turn supported them.” sustainable food practices to the bright young learners at Prairie du Chien’s B.A. Kennedy Elementary School.

sustainable food practices to the bright young learners at Prairie du Chien’s B.A. Kennedy Elementary School. and with that they were able to hire an executive director and create a membership of both downtown businesses and community members.”

and with that they were able to hire an executive director and create a membership of both downtown businesses and community members.” sustainable community [is] a community that … feeds itself, if you will, that keeps its energy churning and building here rather than going elsewhere.”

sustainable community [is] a community that … feeds itself, if you will, that keeps its energy churning and building here rather than going elsewhere.”

Flash River Safari was featured on CNN International’s weekly citizen journalism show “iReport for CNN” this past weekend. To view the segment

Flash River Safari was featured on CNN International’s weekly citizen journalism show “iReport for CNN” this past weekend. To view the segment

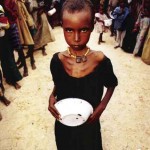

“They heard rumors of a famine creeping across southern Somalia, [and] they wanted to visit the region themselves and see if there was any truth to the stories,” explained Kathy Eldon, Dan’s mother. “[He] was in Kenya for the summer, before returning to UCLA that autumn to continue his studies, [and] was utterly stunned by what he saw – hundreds of dead and dying women, children, and old people; thousands displaced in a desperate search for food. Although barely able to view the horrors unfolding before him, he shot them with his camera and they were among the first to be seen by a global audience. Moved by the response to his images, Dan returned again and again to Somalia, recording the aid that flowed into the country- and its decline into chaos. He never returned to UCLA.”

“They heard rumors of a famine creeping across southern Somalia, [and] they wanted to visit the region themselves and see if there was any truth to the stories,” explained Kathy Eldon, Dan’s mother. “[He] was in Kenya for the summer, before returning to UCLA that autumn to continue his studies, [and] was utterly stunned by what he saw – hundreds of dead and dying women, children, and old people; thousands displaced in a desperate search for food. Although barely able to view the horrors unfolding before him, he shot them with his camera and they were among the first to be seen by a global audience. Moved by the response to his images, Dan returned again and again to Somalia, recording the aid that flowed into the country- and its decline into chaos. He never returned to UCLA.” “I learned that when you’re a journalist, you get to save people’s lives,” explained Ruqiya. “Not physically, but emotionally – because there’s people

“I learned that when you’re a journalist, you get to save people’s lives,” explained Ruqiya. “Not physically, but emotionally – because there’s people President Abdirahman Mohamed Mohamud‘s question to the girls and their class was if they had plans to come back to Somalia. The girls told me that they smiled broadly when asked this question, answering together, in unison: “Yes, we do want to go back to Somalia … We want to make a difference.”

President Abdirahman Mohamed Mohamud‘s question to the girls and their class was if they had plans to come back to Somalia. The girls told me that they smiled broadly when asked this question, answering together, in unison: “Yes, we do want to go back to Somalia … We want to make a difference.” Jesse represents three generations of river-men who presently man their set of two tow boats and multiple barges – a local family run business who represent over 100 years of experience working the river between them.

Jesse represents three generations of river-men who presently man their set of two tow boats and multiple barges – a local family run business who represent over 100 years of experience working the river between them. The islands are comprised of a layer of sand which is dredged from up stream in the river, a layer of rock, followed by the planting of native grasses and rows of willow trees to help buffer the island while attracting a number of waterfowl, turtles and fish.

The islands are comprised of a layer of sand which is dredged from up stream in the river, a layer of rock, followed by the planting of native grasses and rows of willow trees to help buffer the island while attracting a number of waterfowl, turtles and fish. (11/28/07)

(11/28/07) Starting from the Brian Coyle Center of the University of Minnesota where Somali children of all ages worked on computers, talked music, and played basketball, we moved through the inner-city landmark of Cedar-Riverside Plazas, a low-income housing set of buildings – all colorful beyond belief – which have been reclaimed from a once drug/gang infested stronghold. “You used to not be able to enter that area,” explained Ms. Hakeem, who ran for City of Minneapolis Mayor back in 2005 under the Green Party banner. “But now you can walk around freely, even at 10pm at night. When the Somali refugees began to arrive, they naturally moved into the least expensive section of town – Cedar-Riverside.”

Starting from the Brian Coyle Center of the University of Minnesota where Somali children of all ages worked on computers, talked music, and played basketball, we moved through the inner-city landmark of Cedar-Riverside Plazas, a low-income housing set of buildings – all colorful beyond belief – which have been reclaimed from a once drug/gang infested stronghold. “You used to not be able to enter that area,” explained Ms. Hakeem, who ran for City of Minneapolis Mayor back in 2005 under the Green Party banner. “But now you can walk around freely, even at 10pm at night. When the Somali refugees began to arrive, they naturally moved into the least expensive section of town – Cedar-Riverside.”  Part of learning about pride in your community comes from actively pitching in to help it out. As we moved along the streets and under the bridges, Ayan and Mary introduced me to their latest community project – a mural of Minneapolis they are working on in conjunction with “Articulture”. Here, Executive Director Elizabeth Greenbaum explained that when it comes to at-risk kids mixed with art, “art is a wonderful equalizer, especially for students who don’t succeed in other subject matters. When you think about it and take it a step further, we’re talking about the basic understanding and the basic concepts to write – and that leads into reading and that leads into learning – so [the] arts are very much orientated to learning on all levels.”

Part of learning about pride in your community comes from actively pitching in to help it out. As we moved along the streets and under the bridges, Ayan and Mary introduced me to their latest community project – a mural of Minneapolis they are working on in conjunction with “Articulture”. Here, Executive Director Elizabeth Greenbaum explained that when it comes to at-risk kids mixed with art, “art is a wonderful equalizer, especially for students who don’t succeed in other subject matters. When you think about it and take it a step further, we’re talking about the basic understanding and the basic concepts to write – and that leads into reading and that leads into learning – so [the] arts are very much orientated to learning on all levels.” Relay for Life is in association with the

Relay for Life is in association with the  At the age of 36, one town cancer survivor, Kathie Smith, a mom of two young children, explained that it was Austin Price, a young boy who was diagnosed with cancer at age 4 1/2, who “paved the way for my kids to handle me being diagnosed with cancer.” “I graduated from high school together with [Austin’s mom] and Austin was in day care with my children. He taught my kids that just because you have cancer [it] doesn’t mean it’s fatal.” Somewhat of a living legend here in Aitkin, Austin, now age 6, has survived a year following eight months of hospitalization and treatment down at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis. “He’s made it,” beamed Kathie, fighting back tears.

At the age of 36, one town cancer survivor, Kathie Smith, a mom of two young children, explained that it was Austin Price, a young boy who was diagnosed with cancer at age 4 1/2, who “paved the way for my kids to handle me being diagnosed with cancer.” “I graduated from high school together with [Austin’s mom] and Austin was in day care with my children. He taught my kids that just because you have cancer [it] doesn’t mean it’s fatal.” Somewhat of a living legend here in Aitkin, Austin, now age 6, has survived a year following eight months of hospitalization and treatment down at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis. “He’s made it,” beamed Kathie, fighting back tears. When asked for advice for others who might be fighting for their very lives around the world, Austin, moving between examining the camera and sitting on his mother’s lap, rubbed his head before answering: “Be strong” – to be followed by the simple, hard fought admonition – “be brave.”

When asked for advice for others who might be fighting for their very lives around the world, Austin, moving between examining the camera and sitting on his mother’s lap, rubbed his head before answering: “Be strong” – to be followed by the simple, hard fought admonition – “be brave.”